|

Originally posted March 2018.

"What You Read" is a short story which will be released in ten parts in this blog. It is inspired by the work I did for “The Pendulum”. It revolves around the question of what the books we read say about us. I wondered whether on the estates your husband and his comrades stole in the name of the Reich in Poland, you listened to Mann’s BBC radio broadcasts, imploring the German people to awaken from their fateful sleep. To do so was illegal, but as the senseless war turned against Germany, increasing numbers listened in private to this literary giant, who lived in exile with his Jewish wife in America. Did you dismiss his revelation that people were being gassed down the road from you as the influence of ‘decadent’ America on his mind, or did your nightmares begin then? Did you wonder about the ill-smelling haze from the chimneys that drifted overhead, or did you dismiss it as greasy smoke? “The Holocaust was a conspiracy by the international media to keep Germany down,” you once told me, offering what you regarded as an appealing alternative truth. As you said these words, you will have recalled Toni’s reference to “the secret scandal, that feeds on oneself in the quiet and that devours self-respect.” Her call for “uprightness and openness” would have grated on you, as you delivered this explanation to me that you knew was false. In that moment, it must have been terrible to be so well read. It was easy to blame the males for everything, but inwardly you must have contemplated your role in the fall of the family, and in the ill-fated Brazilian adventure. Despite the security you and your husband had built up through your business and home outside of Hamburg after the war, the renewal of war crimes trials in the late fifties put both of you under pressure. The argument that one had simply followed orders, and therefore could not be regarded as responsible, fell on deaf ears. There was no knowing where this might end, and so you both took the extended hand offered by a former SS-comrade who seemed to be living the good life far away under the sun. Toni followed you in every move you made, with her encouragement of ill-fated transactions between men that she thought would benefit her, but that eventually resulted in the sale of the grand family home, and the scattering of the remaining members in different directions. Despite this, Toni never let go of her aspirations, as impossible as they had become. Neither did you, and while I can rail at you for your apparent lack of remorse, this is what kept you alive, so that I too could gain a glimpse into what had preceded me: the golden age of Hamburg merchants and the thousand-year Reich, which in their preoccupation with infinity were destined to end.

0 Comments

Originally posted March 2018.

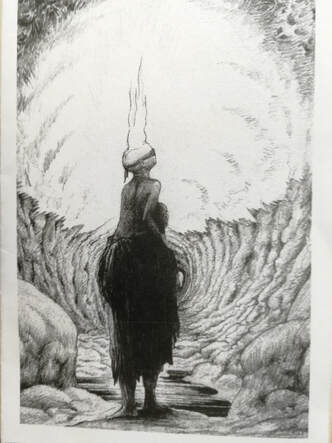

"What You Read" is a short story which will be released in ten parts in this blog. It is inspired by the work I did for “The Pendulum”. It revolves around the question of what the books we read say about us. It was a pocket-sized hard cover with a mauve-colored flap that you gave to me for my sixteenth birthday. On the front was a sketch of a woman in a bonnet on the arm of a man in a top hat making their way through the narrow streets of old Hamburg. This was the city as it looked before you left it for Poland in the spring of 1940, and as it had been for centuries, before Allied bombs flattened it three years later. Above the sketch was the subtitle, “The Decline of a Family,” which didn’t strike me until many years later. At the time, you proclaimed that Thomas Mann’s “Buddenbrooks” was the best crafted novel you had ever read, and that Mann was without question Germany’s most gifted novelist. “But strange about his private life,” you muttered with distaste, and didn’t elaborate. None of these comments could entice an impatient sixteen-year-old to endure the unending sentences in German. The book went out of the wrapping paper straight into the book shelf, only to be removed twenty-seven years later when the subtitle began to haunt me. You’d left your husband in the interior of Brazil, your marriage long broken, your eldest gone, with your remaining children scattered across the continents. The dreams of living space and abundant resources had been dashed by the self-defeating nature of greed, and you lived in your small apartment, like a lady of the manor in parody, staring at a grand painting in a heavy, baroque frame of men in a golden field. It was in your very last years that the shoe-horning of old dreams into present realities became most apparent. One of your children, who had no family of her own, cared for you day and night, and often you’d scold her about the quality of her service. I preferred to think that this was just your frustration with the growing confines of age, but one couldn’t help the feeling that in your attitude were the last traces of overlordship from a bygone era. Increasingly, when I visited and watched you from across the dining table, I saw one of Picasso’s women, whose face, with its many angles, could never be ascertained. In the lives of the Buddenbrooks family I caught a glimpse of one of those facades. It revealed your young woman’s aspiration to live the life of the elegant Hamburg merchanting class, and to stroke your hand across the light yellow upholstered sofa - a color reserved for the privileged - in Toni Buddenbrooks’ childhood home. In the beginning, your husband seemed to offer you a comparable possibility, as he managed his father’s successful chocolate business, and drove through town in a Wanderer, a luxurious German brand car. That was until the Depression struck, and your angry spouse signed up for the Party just a few days before the bewildering Christmas of 1931. I wondered whether you had been able to keep a copy of “Buddenbrooks” in your home under the Third Reich. This wasn’t because no one had one. On the contrary, like all other books that were banned and burned during the thirties, everyone had copies. In fact, there had never been as thriving a business for books in Germany, legal and illegal, as during that time when people sought a temporary escape from the impending new war. Yet, in your household it may not have been possible. You and your husband had cast your fates with the Party and its elite from the beginning, and the daily demonstration of loyalty demanded the rejection of the intelligentsia, particularly Jews or those who had married them. Blood and Land became your mantra, so that your husband could realize his dream of leaving the ‘decadent’ city and the chocolate business, and becoming an influential landowner.  Sometimes you meet someone who does things just because they need to be done, who explores and pursues ideas fearlessly wherever they may go, and who looks around into the fine detail of everything, into its brokenness, and feels the sublime whole. That person is hope. Fly, fly, fly Peter Tucker. How we will miss you. Godspeed, my friend. Image: "Hope" by artist and philosopher, Peter Tucker (1942-2019) In Svenska Dagbladet, 2007: https://www.svd.se/slottsparkens-baste-van Originally posted March 2018.

"What You Read" is a short story which will be released in ten parts in this blog. It is inspired by the work I did for “The Pendulum”. It revolves around the question of what the books we read say about us. Yet this small victory hadn’t saved you from harder things to come. “You cannot describe depression,” you said, and then went on to describe it. “It is a terrible thing; you don’t want to see anyone, or do anything. The day has no beginning and no end. One cannot wish it upon anyone.” Our conversation prompted me to read Effi Briest, and to learn of her world of paranoia and superstition that grew out of her confinement in a relationship and in a place she didn’t want to be in. Her fear that she was being haunted by the unrequited spirit of a Chinaman, who had come to the North Sea shores on a trading ship and died in her husband’s house, nearly drove her mad. You knew what it was like to stand on the brink of madness, and could take Effi’s predicament to yourself. What had begun as a titillating novel about someone else when you were a youngster, became a terrifying mirror. You kept to your superstitions, such as spending considerable periods of time holding a pendulum, a tiny magnet tied to the end of a piece of silk string, over the image of your son whom you were certain had died in the Brazilian wilderness. You insisted he was dead because the pendulum had told you so, and again I furled my eyebrows at the ferocity of your pain. I didn’t like superstition, but something in me couldn’t reject the possibility that the dead Chinaman and the tiny magnet might just have some power over us. The part you didn’t tell me about yourself was the part I learned from reading about Effi’s life, and what surrounded us in your apartment. Your sterling silver, the gold-rimmed plates and your blue satin bathrobe that hung in your oak closet, struck me as much as anything else each time that I visited. From the beginning, like you, Effi only wanted the best or nothing. Her desire was your desire, and it was this that attracted you to your husband and his ideology, which became the nemesis of your soul. It made you question whether you really were a victim, and wonder whether, like Effi’s critics, you had deserved what you had got. It was a mystery to me that an independent thinker like you, who saw the injustice of Effi’s fate, could marry a man whose ideology dictated that you and other women could only become heroes if you became slaves. Yet the answer lay in the story of Effi Briest itself. He had offered you the best, “only the best”- you said, he'd said - and you followed him in pursuit of this as he and his comrades grabbed land and murdered its owners in Poland, and eventually drove the family to ruin pursuing megalomaniac dreams in exile in Latin America. You didn’t tell me all of these things. Instead, I found them out myself in archives and among eyewitnesses. At over one hundred years of age, when death faced you each day, you asked the same question as Effi had on her deathbed: “Will God take me?” For both of you it was a rhetorical question. Neither of you believed that he would, because you saw yourselves as justifiably guilty, not as innocent victims. Suddenly, I thought I understood why you said that the Pope should be shot. He was the anointed keeper of the entrance to God's house, from which you believed you had been expelled forever. Through Effi Briest I was able to distil the source of our guilt, which had trickled down from you, to the generation between us, and eventually to me. Was this just or unjust, and must the sins be paid for by the suffering of the generations? If I had been deeply superstitious, I would have said that we had no choice but to accept it. Yet I am only mildly so, and continue to seek another way of framing the question. Originally posted February 2018.

"What You Read" is a short story which will be released in ten parts in this blog. It is inspired by the work I did for “The Pendulum”. It revolves around the question of what the books we read say about us. You were as secretive an adolescent as I was. We both had our reasons. You chose to escape from under the pall of indignity that was draped over your nation’s soul to the bright window in the attic of your parents’ farmhouse, where you sat and devoured forbidden novels. The adults around you knew that you were bookish and said it was unbecoming of a young girl to read so much. It would needlessly trouble the mind and detract from household chores. I carved out my own corner in whatever country my family was living in, burying myself in letters to friends left behind, that were like a cry for stability. A flustered parent, indignant at the damning history you and her father had left to her, stood outside my door. One of her mechanisms for coping was to call me overly-sensitive, among other things, and to insist that I must toughen up. When first you mentioned Fontane’s novel, Effi Briest, to me, you shook your head. “Dreadful story – a poor girl married off at the age of seventeen by her parents to her mother’s former lover, a baron old enough to be her father, and stashed away in a North Sea outpost where he served as District Counsellor to the Prussian administration. Now tell me, what could be expected of her?” you asked. Effi’d had a risky affair with a dashing, womanizing major and was never again permitted to see her daughter, expelled from the same intransigent Wilhelmine German society as the one you had been born into. Eventually, she was accepted back into her parents’ home and there died young of heartbreak. “I read it when I was a girl without my parents knowing,” you added, and blushed as you mischievously looked askance over the edge of your coffee cup. Suddenly, you seemed very modern to me. While others of your generation said that Effi got what she deserved for her infidelity and, above all, for challenging the status quo of laws and social codes, you saw her as a victim. You believed in her natural rights to long and not to be abused. You were a deeply sexual being, even as an old woman. I saw you in your laced silk chemise and stockings attached to a garter belt as you dressed. Into your nineties, you were a picture of sensual beauty. Your war had taken place in the bedroom, and as you scratched at the pressed cream damask on your dining table, without looking at me you said: “It wasn’t pleasant – our life together. He would come at me angry and drunk, and once he was done returned to his Polish girls.” You scratched faster, as though it could dull the hurt. “Five children – one after the other - it was expected in those times. The pains were appalling!” I hadn’t borne any children yet, but vicariously felt your pain in my abdomen. “He found another side-fling in Brazil – a mulata – and then I left. In the mortuary, after he’d died, they put shoes on him that were too big for his small feet.” Your nostrils flared with resentment, and perhaps some mild satisfaction that in the end you had seen him emasculated. |

AuthorSee About. Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed