|

You cannot predict the world

Or a day or an hour or a nanosecond, Or where the bird will fly or the seed will fall, Or exactly how fast the butterfly’s wing will flutter, Or what color the honey will be this year, Or whether there will be rain tomorrow. The ego craves a pattern, To know beforehand, how things will revolve around itself, Even evolve around itself, But that is a dead end for delusionals and dictators. Not knowing is alive, Creeping, gnawing, decaying, growing, remolding, metamorphosing Becoming, in every conceivable unit of time, not itself, Pressing on and around like waves or quicksand or water in cracks between fingers, Or air or clouds, not there as soon as you are in them, Or touching a horizon and discovering the marvel of its disintegration. Image below: Reflection of birch and sky on the still lake off my island.

1 Comment

Away, troubled time,

Rage of storms roiling Melt, winter armor, So I may touch my skin Sink, grey clouds, Into memory’s deep waters Recede, ice, from my senses So light may flow within. On the island, Good Friday 2024. Flags billow and fade

Into one another, Colors bleeding In the winds of war. In peacetime, they hang limp, Separate, The colors keeping to themselves In the dense silence before a new fight. A craggy, ancient language Bursts from a man’s chest, Haunting in its tenderness From which the angry passion of belonging rises. Mothers’ warm tears trickle through time And the dank crevices of stone walls Into the tranquil sea, The final resting place of children. Upon driving past a row of flags billowing in the wind in the Pyrénées-Orientale. There is forgiveness in the mountains,

In the craggy face Where the ice of a broken heart melts With each new spring, Trickling through, down, down Into the meadow So the donkeys may graze, bear food to the market, and the toothless vendor may smile. On walking in the foothills of Le Canigou at the outset of 2024.

Tendrils hold one another, timeless art expands my split second-- Margot Fonteyn’s arms pushing out the borders. A bee burrows into a cucumber flower, deliriously clear, moisture dampens the buzzing. STOP A heat wave hits three continents STOP More than 100 Barbie dolls are sold every minute STOP A global warming “tipping point” is closer than once thought STOP Raindrops jump on the lake’s surface, a tern hunts in thunder, while a heavy-headed rose bows under the downpour. Miniature frogs take to the paths, pilgrims among the slick leaves, prophesying autumn. STOP As the world boils, a backlash to climate action gains strength STOP The hottest July STOP Why Barbie Must Be Punished STOP The aroma of tomatoes is stark and forbidden, a wild aphrodisiac, making roots heave. The sting of nettle drowns in the rotting, needles dissolve into a smoothie for the soil. STOP Trump is crushing GOP rivals STOP Barbie on Bitcoin STOP Elon Musk’s geopolitical clout STOP Beans bend the corn, in tangled, heavy stocks, submitting to gravity. Golden hairs—a child’s or a witch’s? —befuddle the ants over sheaths of white kernels protected by a stiff green glove. STOP Trump is indicted, again STOP Elon Musk on ‘white genocide’ STOP Summer of Barbenheimer STOP Under the succulent grass is the straw bed, a memory of the summer’s moods, cushioning the earth. Chantarelles defy the contraction, African ochre in the musty decay, skirts of whirling dervishes. STOP How Quran Burners Got the Global Attention They Wanted STOP A Wedding Pushes Through Despite Floods STOP What’s in Trump’s Head STOP Honey oozes through the sieve-- wax, pollen, and the dead, all, work for ants. Too-slow or too-fast, too-long or too-short, nonsensical in the sweet lava-- yearning toward sugar crystals. STOP Ukraine and Russia expand the battlefield STOP Can carbon dioxide removal save us? STOP Barbie’s 1 Billion Dollar Box Office Haul STOP Morning brings the rhythmical rounds-- stir the honey, water the greenhouses, clear the debris, rinse off the dirt. Relinquish the conquest! Spiderwebs will be cotton candy in the corners, butterflies will leave their eggs in the kale. STOP Disaster in Hawaii STOP What Should You Do with an Oil Fortune? STOP She Wants to Burn Down Hollywood STOP Warmth returns, feeding the illusion, a dream of never-ending summer. Bushes re-bud—could play be forever? -- but the gentle air holds the tension, tired flowerpots betray our make-believe. STOP Ukraine’s War of Attrition Draws Parallels to WWI STOP Death Toll in Maui Wildfires Rises to 89 STOP Gen Z’s Housing Anguish STOP Wasps lick wood, hungry for the cracks in a life of twenty-two days. Hornets scavenge for light, under the window latticing, sun-seeking tourists. STOP America’s Obsession with Monster Trucks STOP Trump Hit with Racketeering Charges STOP The Ruble is in Rubble STOP The mature sun’s glory bleaches highlights in the birch, stroking the greying water. The roses try for another round, but their flowers are small, their scent timid in air that smells of burnt sugar. STOP See the Powerful Storm’s Latest Path STOP India’s Moon Landing Sets the Tone for A New Type of Space Race STOP Trump Inflated Property Values by $2.2 Billion STOP The storms have come, but the morning’s immersion continues-- The wind slices off the tips of waves, freshening my face. The summer is over, but there is still time, always time, neither friend nor foe, a condition that softens us. STOP Punctuation is too expensive STOP We don’t have time for it STOP We’d like to stop STOPPING, but we can’t STOP A telegram from August 2023. At your feet,

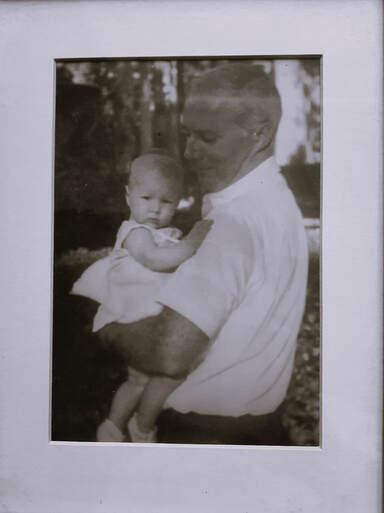

Curled up on the floor pillows, My spinal fluids carry the message – it’s safe. Half asleep The smell of sweet tobacco Drifts over me in our opium den, yours and mine. A storm rages around the corner, Outside, the smell of fuselage Threatens this dream of peace with endings. In my room are the empty boxes Hungry for my doll whose hair I cut away -- For there is no turning back. Your slippers watch “Mutiny on the Bounty,” Loyal pets beside your reclining chair, Their parallel-ness is my lifeline. I pound to be let back in, From the world, I can’t control, But the air is cold and hard -- you’re gone. Through a hole in the fog of my breath on the window Our den is a home for mice -- Only your tobacco pouch remains in my pocket. Remembering my father. Listening to the sounds of his country,

childhood, summer Once more on the radio. Tears swell over bloodshot eyes, Lips quiver At a voice of his ilk, his time, his stripes. One that heard the young and the old, Offered itself as a stage For an autistic youngster to sing. The forgotten rhythms of an old way of talking Charm the heart of a foreigner Weary of too many me's. A ditty rings out the golden hour, Bittersweet as the picture of a gramophone with its shell-like horn On white linen where a wasp devours a strawberry's flesh. On watching an old Swede listening to one of the better programs on "Sommar," Sweden's favorite summer radio program. A thing is at its most beautiful

When it is already dying, The aura is brightest In the knowledge of death's shadow. Hands caress the dance Because it is not forever. A mother's birthing cries Portend the pain of endings. Only love can bear the burden Of a petal's mortality. Some hearts won’t stop beating,

Even a massive dose Can’t take the Marilyn Monroe out of them. Thoughts flicker, Candles in the wind, What was it about her that remains inextinguishable? Two pink bandages Wrapped around her forelegs, cover the holes they made, Blood trickles from my forearms. “Live! Live! Live!” She barks at me from the floor, Hind legs splayed, heart stilled. For a beloved creature I once knew whose keen intellect was always guided by her heart. |

AuthorSee About. Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed